In today’s competitive and fast-changing markets, a well-structured plan is more than a document—it is a decision-making framework that aligns ambition with execution. Practical business planning tips help leaders convert ideas into measurable priorities, clarify resource needs, and reduce uncertainty while preparing for growth, disruption, and stakeholder expectations.

A strong strategic foundation starts with rigorous analysis: defining a clear value proposition, validating assumptions through due diligence, and understanding customers, competitors, and constraints. Evidence-based planning supports realistic objectives, highlights key risks, and establishes performance indicators that strengthen accountability. Above all, planning creates focus by separating high-impact initiatives from distractions.

What follows is a set of business planning tips designed to strengthen strategic clarity and operational readiness. By connecting financial projections, governance, timelines, and contingencies, the goal is to support consistent execution across teams. With a disciplined approach, businesses can shift from reactive choices to a repeatable process that sustains long-term resilience.

Defining Vision, Mission, and Measurable Strategic Objectives

Market conditions will change—often faster than forecasts can keep up. What keeps decisions consistent is a clear vision, a grounded mission, and objectives that translate intent into action. Without that structure, teams can stay busy while drifting away from what actually creates value.

To create direction that holds under pressure, this section focuses on turning ambition into concrete priorities employees can act on, investors can evaluate, and leaders can measure.

Clarifying Long-Term Value Proposition and Competitive Advantage

Before anything can be measured, the organization needs a coherent “why us?” that lasts beyond a single quarter. Defining a durable value proposition and the advantage that protects it gives planning a stable anchor for trade-offs and investment decisions.

A useful way to sharpen this is to separate customer value (the outcomes you improve) from competitive advantage (why rivals can’t easily copy it). “Fast delivery” may describe value; the advantage could be a proprietary routing system, exclusive warehouse locations, or scale economics. As Harvard Business Review (Michael E. Porter) notes, strategy requires choices and trade-offs—so a strong foundation also clarifies what you will not do.

To make the proposition usable in planning, pressure-test it with evidence rather than internal enthusiasm. Seek behavioral proof (conversion rates, retention, willingness to pay) and constraint-aware differentiation (regulatory barriers, supplier leverage, switching costs). When the advantage is real, it becomes the logic behind where to invest—and where to stop investing.

- Define the customer problem in outcome terms (time saved, risk reduced, revenue increased), not features.

- Specify the edge: cost position, speed, network effects, brand trust, or unique capabilities.

- State the trade-offs explicitly to prevent strategy dilution (e.g., “We will not compete on lowest price”).

- Test defensibility with a “copycat” question: how quickly could a well-funded competitor replicate this?

“The essence of strategy is choosing what not to do.” — Michael E. Porter

Translating Goals into SMART Targets and Key Results

With direction defined, the next challenge is keeping it from staying inspirational but non-operational. Converting vision and mission into measurable commitments ensures teams can track progress consistently and adjust before small misses become structural failures.

Begin with a small set of strategic objectives (often 3–5) that reflect the value proposition’s “engine.” Next, define SMART targets—Specific, Measurable, Achievable, Relevant, and Time-bound—and attach key results that reveal progress early, not only at year-end. When metrics are designed well, ambiguity drops: teams know what “good” looks like, and leaders can intervene sooner.

Consider a B2B SaaS firm competing on reliability. One objective might be becoming the most trusted provider in its niche, with SMART targets such as raising service availability to 99.95% within two quarters and reducing average incident response time to under 20 minutes. Pair those with key results tracking leading indicators—change failure rate, on-call load, and post-incident recurrence—so the organization manages systemic risk rather than chasing lagging outcomes.

- Objective: Expand in mid-market without eroding margins.

- SMART target: Increase mid-market ARR by 25% in 12 months while maintaining gross margin above 70%.

- Key results: Improve qualified pipeline coverage to 3.0×, lift win rate by 5 points, and cut CAC payback to < 12 months.

To keep targets actionable, connect each one to an owner, a cadence, and a decision rule. Monthly reviews should answer: Are we ahead or behind? What is driving variance? What will we stop, start, or adjust? When key results tie directly to operating levers—pricing discipline, cycle time, defect rates, churn drivers—strategy becomes a living system rather than a static slide deck.

Market and Customer Analysis as Core Business Planning Tips

Strong objectives still fail if they are built on weak assumptions about demand. Plans become more reliable when they reflect who buys, why they switch, and what changes their decision. Anchoring strategy in market reality also reduces wasted effort on positioning and channels that cannot scale.

Building on the objectives above, this section focuses on two execution-strengthening moves: segment customers using evidence-based profiles, then assess competitors and industry forces that shape profitability.

Segmenting Customers and Developing Evidence-Based Buyer Profiles

Segmentation is where strategy meets reality: it determines which customers deserve priority, which offers can be standardized, and where customization is worth the cost. The aim is to move beyond broad demographics to decision-driven segments and buyer profiles grounded in observed behavior.

Instead of relying on job titles alone, segment on variables that predict purchasing and retention—use cases, urgency, risk tolerance, compliance needs, or total cost sensitivity. In B2B settings, the buying committee matters: the economic buyer, technical evaluator, and daily user often optimize for different outcomes. A cybersecurity firm, for example, may find regulated healthcare buyers prioritize auditability and incident response SLAs, while mid-market SaaS buyers emphasize speed of deployment and predictable pricing.

Because recall is imperfect and preferences shift under constraints, triangulate qualitative interviews with quantitative signals—conversion by segment, churn reasons, time-to-value, and discount rates. As McKinsey & Company highlights, purchasing decisions are strongly influenced by emotional and relational factors, so profiles should capture both functional outcomes and perceived risk.

- Define segment “job”: what progress the customer is hiring the product to make (e.g., reduce onboarding time by 30%).

- Capture constraints: procurement rules, implementation capacity, security requirements, or seasonal demand cycles.

- Document triggers: events that force action (policy change, tool consolidation, rapid headcount growth).

- Quantify willingness to pay: use pricing tests, win/loss analysis, and observed discount thresholds.

To make segmentation operational, write a one-page buyer profile with the top three buying criteria, the “deal-killers,” and the fastest proof points. In SaaS, that might be a 14-day pilot with usage milestones; in manufacturing, it could be a sample run plus a quality certification. Used consistently, these profiles shape messaging, qualification questions, and product sequencing so teams stop guessing and start validating.

Assessing Competitors, Industry Trends, and Barriers to Entry

Customer clarity is only half the picture; competitive dynamics determine whether your advantage holds. Assessing rivals, trends, and barriers to entry helps convert market insight into resource allocation choices rather than surface-level commentary.

One practical step is mapping competitors by customer problem rather than category label. Direct competitors may look similar, but “alternative” competitors often win by changing the model—bundling, vertical integration, or a lower-friction workflow. Many mid-market analytics tools, for instance, compete not only with other platforms but with spreadsheets plus internal BI teams, where switching costs and perceived control can outweigh feature advantages.

Trend analysis is most useful when tied to what changes unit economics or bargaining power: platform policy shifts, new compliance regimes, input cost volatility, and distribution channel consolidation. Privacy regulation, for example, has changed ad targeting, pushing firms toward first-party data and consent-based measurement. When documenting trends, connect each one to a planning implication: “If X continues, we will need Y capability by Z date.”

- Competitive positioning: compare rivals on price architecture, onboarding time, service levels, and ecosystem partnerships.

- Barriers to entry: switching costs, regulatory approvals, proprietary data, network effects, or economies of scale.

- Vulnerability scan: identify where incumbents are slow (legacy tech, poor support, fragmented integrations).

- Strategic signals: funding rounds, hiring patterns, patent filings, and channel partnerships that indicate direction.

To avoid superficial “SWOT lists,” add a replicability test: what would it cost (time, capital, talent) for a well-funded entrant to match your advantage? If the answer is “six months and a few hires,” the plan should emphasize speed, customer lock-in, and distribution. As Rita McGrath observes, advantages can be temporary in fast-moving markets—so differentiation must be treated as something to renew, not declare once.

“In many arenas, competitive advantage is transient. Companies need to learn how to launch new advantages again and again.” — Rita Gunther McGrath

Financial Modeling and Resource Allocation: Practical Business Planning Tips

Clear strategy and market insight still need financial proof. Financial modeling is where ambition meets arithmetic—turning priorities into resource allocation decisions that can be funded, staffed, and sustained.

Rather than chasing a perfect forecast, the objective is to build a model that surfaces the few variables that truly drive outcomes. This section focuses on assumptions, cash discipline, and aligning operating capacity with what the plan prioritizes.

Building Revenue Assumptions, Cost Structures, and Break-Even Scenarios

Credibility begins with assumptions that can be tested and revised quickly. Structuring revenue drivers, clarifying costs, and defining break-even points turns forecasting into a practical tool for go/no-go decisions.

Instead of relying only on “top-down” market sizing, build revenue from unit-level drivers: leads → conversion → average contract value → retention. For subscription models, separate new ARR from net revenue retention; for transactional businesses, model purchase frequency and contribution margin per order. When results trace back to controllable levers, the forecast becomes a management tool rather than an aspirational number.

Costs should also be transparent about what scales and what doesn’t. Fixed costs (base salaries, rent, core tooling) behave differently than variable costs (payment processing, shipping, usage-based cloud spend). As Oracle NetSuite notes, break-even analysis quantifies the sales volume required to cover total costs—useful for evaluating new markets, pricing shifts, or headcount expansion.

- Revenue drivers: volume, price, mix, retention, expansion, and sales cycle length.

- Cost clarity: fixed vs. variable, and which costs rise stepwise (e.g., a second support shift).

- Break-even views: break-even units, break-even revenue, and break-even time (months to cover cumulative losses).

- Scenario set: base / downside / upside with 3–5 linked assumption changes, not 30 disconnected edits.

“All models are wrong, but some are useful.” — George E. P. Box Keep the model useful by documenting assumptions beside the numbers, including the evidence source (pipeline data, historical churn, pricing tests) and the date last reviewed.

Planning Cash Flow, Funding Strategy, and Capital Requirements

Even profitable plans can fail if cash timing is ignored. Cash forecasting, runway thresholds, and aligned funding choices help ensure the plan survives volatility, delays, and working capital swings.

Build a 13-week cash forecast that tracks collections, payroll, taxes, vendor terms, and debt service, then connect it to a longer-range monthly model. Many failures come from working capital gaps—for example, paying suppliers in 30 days while customers pay in 60–90. Growth can create a cash squeeze when receivables expand faster than inflows.

Funding choices should fit business economics and control preferences. Venture capital may accelerate scaling where returns depend on speed and large markets, while bootstrapping or revenue-based financing can better match steadier, cash-generative operations. SVB Startup Insights frequently emphasizes runway planning as governance: set triggers such as initiating cost controls at 6 months runway and freezing hiring below 4 months runway.

- Cash conversion cycle: days inventory + days receivable − days payable (track it monthly).

- Runway policy: pre-agreed actions tied to runway bands to reduce panic decisions.

- Capital requirements: separate capex (equipment, build-outs) from operating losses.

- Stress tests: delayed collections, churn spike, cost inflation, and slower hiring productivity.

Aligning People, Processes, and Technology with Budget Priorities

A model cannot execute—teams do. Aligning headcount, workflows, and systems ensures the budget reinforces strategic intent rather than funding accidental complexity.

Translate strategic objectives into a capacity plan: which roles are critical now, which can be deferred, and which productivity assumptions are realistic. Sales hiring is a common example—new hires rarely deliver full quota in month one, and modeling ramp time (often 3–9 months depending on deal cycle) prevents overestimating near-term revenue while underestimating burn. Process constraints such as implementation bandwidth, onboarding throughput, and support coverage should also be reflected to avoid selling what the organization cannot deliver.

Technology spend is often mistimed when tools are purchased before processes stabilize. Prioritize systems that reduce cycle time, defects, or rework at measurable rates—for example, automated billing to reduce days sales outstanding or improved observability to reduce incident duration. When evaluating software, quantify total cost of ownership (licenses, admin time, training, integration) and treat vendor lock-in as a strategic risk.

- Budget-to-strategy mapping: tag each major line item to a strategic objective (or remove it).

- Operating cadence: monthly variance reviews with decision rules (reallocate, pause, or double down).

- Guardrails: approval thresholds and ROI criteria for hires, tools, and campaigns.

- Execution metrics: cycle time, utilization, quality rates, and customer time-to-value.

To reinforce accountability, assign each budget area an owner, a measurable outcome, and a review rhythm. When finance becomes a shared operational language—not just a back-office report—strategic focus is easier to defend under pressure.

Execution Planning, Risk Management, and Review Cadence

A plan often looks solid until missed dependencies, delayed hiring, or supplier disruption exposes what was never operationalized. Sustained strategic traction comes from execution mechanisms: milestones people can commit to, risks teams can anticipate, and a review cadence that turns learning into course correction.

Building on the financial and market foundation above, this section focuses on delivery infrastructure—coordination across functions, downside protection, and consistent decision-making as reality evolves.

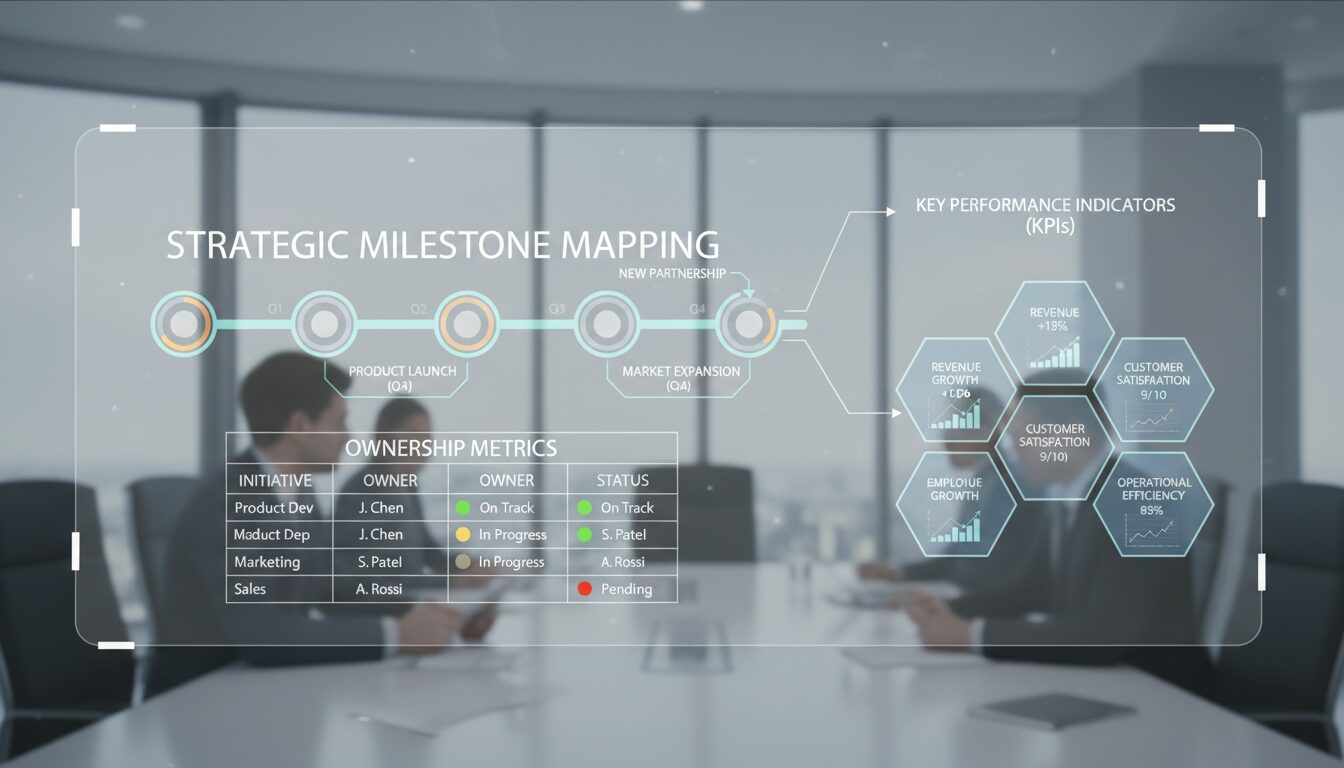

Establishing Milestones, Ownership, and Operational Metrics

Progress depends less on deadlines and more on sequencing. Milestone-based execution, clear ownership, and operational metrics help reveal whether the plan is working well before financial results appear.

Decompose each strategic objective into a short chain of deliverables with clear entry and exit criteria. A practical format is “milestone + proof”: not “launch onboarding improvements,” but “reduce onboarding time from 21 to 10 days with a measured cohort and documented handoffs.” Where programs are complex, dependencies (legal review, data access, procurement, integration capacity) should be tracked explicitly because constraints often drive slippage more than effort does.

Ownership works best when it is unambiguous and paired with authority. Use a lightweight RACI (Responsible, Accountable, Consulted, Informed) only when cross-team coordination is real; otherwise, keep accountability with a single “Directly Responsible Individual” and define escalation paths. This avoids the common failure mode in which multiple teams are “involved,” yet no one is responsible for outcomes.

- Milestone hygiene: define acceptance criteria, dependencies, and a target date with a named owner.

- Operational metrics: include leading indicators such as cycle time, defect rate, and time-to-value—not just revenue.

- Capacity realism: reflect ramp time for hires and implementation bandwidth to avoid over-committing.

- Decision thresholds: pre-define what triggers a pivot (e.g., “if activation stays below 35% for two cohorts”).

A logistics company investing in “faster delivery,” for example, may track on-time delivery rate, scan compliance, and average dwell time at sorting hubs. These indicators surface operational drift early—often weeks before margin erosion appears.

Identifying Risks, Contingencies, and Compliance Requirements

Plans become more resilient when risks are named, monitored, and owned. Identifying failure points early—and defining workable contingencies—reduces surprise and helps protect cash, reputation, and regulatory standing.

Run a pre-mortem: assume the plan missed its targets in 12 months, then list the most plausible causes. Convert those into a short, decision-oriented risk register with probability, impact, and an assigned mitigator. If a risk does not change behavior, it becomes documentation rather than management.

Contingency planning should be specific enough to execute under stress. A SaaS firm exposed to platform dependency, for instance, might define a “Tier 1” plan: diversify acquisition channels, build a partner motion, and create a product-led onboarding path to reduce reliance on paid spend. Where cybersecurity or privacy obligations apply, treat compliance as a design input rather than a late-stage hurdle. Under the EU’s GDPR, fines can reach up to €20 million or 4% of global annual turnover (whichever is higher), as summarized by GDPR.eu guidance.

- Risk categories: market demand, pricing pressure, operational capacity, vendor concentration, talent gaps, and force majeure.

- Mitigation plans: leading indicators, preventive controls, and a named owner for each top risk.

- Contingency triggers: explicit thresholds (e.g., churn +2 points, DSO > 60 days, incident volume spike).

- Compliance checklist: data handling, contract terms, tax nexus, industry-specific rules, and audit readiness.

“The biggest risk is not taking any risk.” — Mark Zuckerberg

Even when that sentiment applies to innovation, disciplined planning adds balance: take risks deliberately, then price the downside with contingencies you can actually execute.

Implementing a Planning Rhythm for Continuous Improvement and Accountability

Execution usually breaks down through inconsistent follow-through rather than lack of intelligence. A steady planning rhythm links weekly signals, monthly decisions, and quarterly resets so accountability stays high without becoming bureaucratic.

Use three distinct cadences with clear purposes. Weekly reviews focus on leading indicators and blockers; monthly sessions cover variance, reallocations, and hiring or tool approvals; quarterly reviews revisit assumptions and strategic fit. The intent is a repeatable “sense-and-respond” loop in which metrics drive decisions and decisions drive changed behavior.

To avoid status theater, structure reviews around a short set of questions: What changed? Where are we off-plan? What is the root cause? What decision is required—and who owns the follow-through? Document decisions as “one-way doors” (reversible experiments) versus “two-way doors” (hard-to-reverse commitments such as multi-year contracts). As Harvard Business Review (Kaplan & Norton) emphasizes, execution improves when measures and management processes are integrated rather than treated as separate initiatives.

- Weekly: review operational metrics, unblock dependencies, and confirm next actions (owners + dates).

- Monthly: analyze KPI variance, update forecast assumptions, and reallocate budget based on evidence.

- Quarterly: refresh priorities, reassess competitive signals, and retire initiatives that are not compounding value.

- Post-mortems: run blameless reviews after major misses to improve systems, not assign fault.

Treating the plan as a controlled experiment is one of the most effective business planning tips: assumptions become hypotheses, metrics provide feedback, and the cadence becomes the learning engine.

Turning Business Planning into a Repeatable Advantage

Business planning becomes a competitive edge when it functions as a decision system, not a one-time document. With clear objectives, evidence-based market insight, and financially grounded trade-offs, teams can stay aligned and adjust quickly as conditions change. When that system is reinforced by ownership, risk discipline, and a consistent review cadence, strategy remains executable—and resilience becomes repeatable.

Bibliography

Box, George E. P. “Science and Statistics.” Journal of the American Statistical Association 71, no. 356 (1976): 791–799.

Kaplan, Robert S., and David P. Norton. “Turning Great Strategy into Great Performance.” Harvard Business Review 77, no. 1 (1999). https://hbr.org/1999/11/turning-great-strategy-into-great-performance.

McGrath, Rita Gunther. “Transient Advantage.” Harvard Business Review 91, no. 6 (2013). https://hbr.org/2013/06/transient-advantage.

Porter, Michael E. “What Is Strategy?” Harvard Business Review 74, no. 6 (1996). https://hbr.org/1996/11/what-is-strategy.

Oracle NetSuite. “Break-Even Analysis.” Accessed August 2025. https://www.netsuite.com/portal/resource/articles/accounting/break-even-analysis.shtml.