Small Business Financial Planning: A Practical, Data-Driven Guide to Cash Flow, Budgeting, Forecasting, and Essential Tools

Small business financial planning works best when you treat it like an operating system: measurable, repeatable, and grounded in real numbers instead of assumptions. In volatile markets, strong products and steady sales are rarely enough—cash timing, cost control, and visibility into future obligations often determine whether a company grows or stalls.

This guide uses a practical, data-driven approach to connect day-to-day decisions with long-term goals. With basic cash flow logic and a few core reports, owners can turn transactions into insight, spot patterns, and set targets that are both realistic and actionable.

Along the way, you’ll learn how to build a budget that mirrors how the business actually runs, create rolling forecasts that update as new information arrives, and monitor leading indicators (like collection speed and inventory turns) that surface liquidity pressure early. You’ll also see common planning mistakes—including optimistic revenue assumptions, ignoring seasonality, and underestimating working capital—plus simple tools and templates you can implement immediately.

Building a Data-Driven Foundation for Small Business Financial Planning

Financial decisions feel uncertain when the numbers look “right,” yet the story behind them is unclear. Most of that uncertainty comes from two sources: unclear definitions (what success means, what constraints apply, which assumptions you’re using) and inconsistent data (categories, timing, and measurement). Before budgets and forecasts become dependable, you need a foundation that turns daily transactions into repeatable insight.

To build that base, focus on four building blocks: clear goals and constraints, reporting categories aligned to operations, a small set of high-signal KPIs, and a monthly close routine that keeps data trustworthy enough to guide cash decisions.

Define financial goals, constraints, and planning assumptions

Stronger planning starts with explicit choices rather than vague intentions. The objective here is to define the targets that shape daily decisions, the constraints that limit options, and the assumptions that must be revised as conditions change.

Translate strategy into financial outcomes. Instead of “grow revenue,” set measurable goals such as maintain 60 days of cash runway, hit 55% gross margin, or cap owner draws at X until debt service coverage is stable. These targets become practical guardrails for decisions like hiring, marketing expansion, or pricing changes.

Constraints should be documented next, because they often predict outcomes more reliably than goals. Common constraints include loan covenants, minimum inventory commitments, seasonal demand swings, or a labor market that forces wage increases. When constraints are treated as first-class inputs, the plan is less likely to “work on paper” while breaking in cash timing.

Capture assumptions and assign ownership for keeping them current. Useful planning assumptions include:

- Sales cycle length and expected close rate by channel

- Collections behavior (e.g., typical days to pay by customer segment)

- Supplier terms, freight variability, and minimum order quantities

- Capacity limits (billable hours, machine throughput, delivery constraints)

- Cost inflation for key inputs (labor, rent, utilities)

Visible assumptions are easier to stress-test and update. As the U.S. Small Business Administration notes in its financial management guidance, revisiting the drivers behind performance—not just producing statements—helps owners respond sooner to shifts in demand and costs.

Set up a chart of accounts and management reporting categories

Most reporting problems aren’t caused by software limitations; they come from inconsistent categories. Aligning your chart of accounts to how you manage the business makes it easier to see margin, overhead, and cash drivers without rebuilding reports each month.

Structure categories around recurring decisions. If you routinely compare lead sources, split revenue by channel. If pricing is the key lever, track by product line or service package. If labor is the constraint, separate direct labor from overhead payroll. The goal is not complexity—it’s decision-useful visibility.

Keep the general ledger straightforward, and use management “dimensions” such as classes, locations, or tags (available in many systems). For example:

- Income: split by product/service line and recurring vs. one-time revenue

- Cost of Goods Sold: materials, direct labor, subcontractors, fulfillment fees

- Operating Expenses: sales & marketing, G&A, rent, software, insurance

- Other: interest, taxes, one-time items (kept separate for clarity)

Operations should drive the final categorization choices. A retailer may isolate shrink and markdowns; an agency might separate billable and non-billable labor; a manufacturer may break out scrap as its own cost line. Categories that mirror controllable drivers tend to produce forecasts that hold up under real-world pressure.

“Accounting is the language of business.” — Warren Buffett

Establish KPIs and baselines (cash conversion cycle, gross margin, burn rate)

With consistent categories in place, KPIs become far more predictive. The goal is to choose a small set of metrics that surface cash pressure early, then establish baselines so changes are interpreted as trends rather than noise.

Use a baseline period—often the last 6–12 months—and calculate KPIs monthly to see trend lines instead of isolated snapshots. This answers a critical question: “What is normal for us?” Without that baseline, teams either overreact to normal variation or miss slow deterioration.

Core KPIs to implement:

- Cash Conversion Cycle (CCC): how long cash is tied up in operations. A common formula is DSO + DIO − DPO (days sales outstanding + days inventory outstanding − days payable outstanding). When CCC rises, growth can consume cash even if profit looks healthy.

- Gross Margin: (Revenue − COGS) ÷ Revenue. Track by product line and customer segment to identify “busy but not profitable” work and support pricing decisions.

- Burn Rate: average monthly net cash outflow (or net operating loss) when expenses exceed inflows. Pair it with runway (cash on hand ÷ burn rate) to quantify how much time you have to adjust.

Baselines clarify the “why” behind cash stress. If average gross margin is 48% and it drops to 42% for two months, the driver may be discounting, higher fulfillment costs, or unbilled labor—not sales volume. Similarly, a CCC increase from 35 to 55 days can explain a shrinking bank balance despite rising revenue: cash is getting trapped in receivables or inventory.

Create a monthly close cadence and data quality checks

Timely decisions require timely numbers, but speed without accuracy creates expensive confusion. A lightweight monthly close process, paired with a few quality checks, makes your reports reliable enough to support budgeting and forecasting.

Set a consistent cadence by closing the prior month within 5–10 business days. This window keeps trends actionable while allowing time to capture missing invoices and payroll detail. Consistency matters as much as speed—leaders trust reporting when it arrives predictably.

A practical monthly close checklist includes:

- Reconcile bank and credit card accounts to the statement

- Review accounts receivable: past-due list, credits, unbilled work

- Review accounts payable: unpaid bills, vendor credits, upcoming payments

- Record inventory adjustments (or validate counts/costing method)

- Confirm payroll allocations (direct vs. overhead) and benefits

- Separate one-time items so trends reflect ongoing operations

Before sharing reports, run simple “quality gates.” Look for unusual spikes, duplicate vendors, miscategorized expenses (for example, software posted to COGS), and timing distortions such as annual insurance recorded in one month instead of amortized. A quick variance scan—current month vs. prior month and vs. the same month last year—often surfaces issues faster than detailed transaction reviews.

With these routines in place, planning conversations shift from “whose numbers are right?” to “what actions do we take?”—because the data is consistent enough to trust.

Cash Flow Management in Small Business Financial Planning

A business can look profitable and still feel cash-tight because cash is governed by timing. Invoices are paid later than expected, inventory arrives before it sells, and payroll hits on schedule regardless of collections. The goal of this section is to make timing visible and manageable through forecastable, controllable cash drivers reviewed weekly.

From that foundation, you’ll build a short-horizon forecast, model inflows and outflows using realistic lags, and identify working-capital levers that improve liquidity without forcing growth-killing cuts.

Build a 13-week rolling cash flow forecast

Budgets set direction; a 13-week cash forecast acts like an instrument panel. A weekly view makes near-term obligations clearer, highlights shortfalls sooner, and forces assumptions about collections and spending to be explicit.

The mechanics are straightforward: track beginning cash + expected inflows − expected outflows = ending cash by week, and roll it forward every Monday (or at close of business Friday). Because the forecast is rolling, week 13 becomes week 12 next week, and a new week is added at the end—so visibility stays constant.

For usability, organize the forecast into decision-grade buckets rather than dozens of lines. A typical structure:

- Beginning cash: bank balances plus any known transfers

- Inflows: customer receipts (by major customer/channel), other income, tax refunds

- Outflows: payroll, rent/occupancy, inventory/COGS payments, operating expenses, taxes, debt service

- Ending cash and minimum cash threshold (your “floor”)

To keep it grounded, reconcile forecasted cash movement to actual bank activity each week. When receipts slip, the update cycle quickly reveals whether the issue is billing cadence, customer behavior, or internal follow-up—and the next weeks can be adjusted immediately.

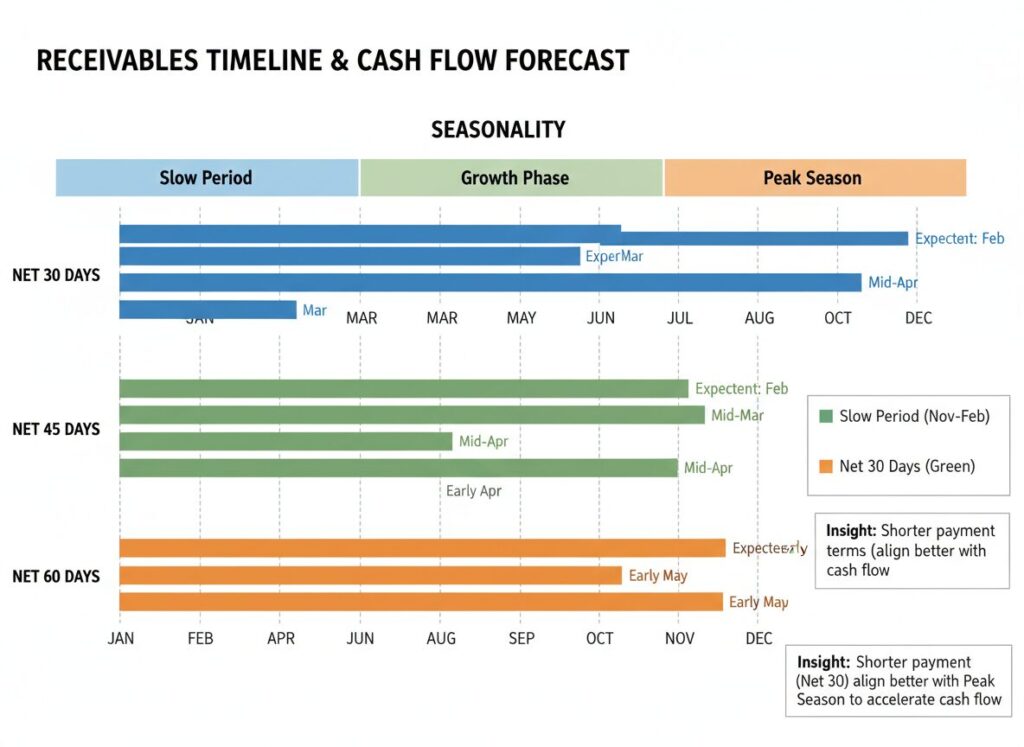

Model inflows: receivables, sales cycles, seasonality, and payment terms

Revenue is not the same thing as cash. Bank deposits depend on invoice timing, payment terms, and customer payment behavior—often shaped by their internal processes rather than yours. Converting sales activity into expected receipts requires lag assumptions that you can validate against data.

Start by segmenting accounts receivable. Because a single average can hide concentrated risk, group receivables by:

- Current vs. past due (0–30, 31–60, 61–90, 90+)

- Top customers (concentration matters more than averages)

- Terms (due on receipt, Net 15/30/45/60)

- Invoice type (subscription, milestone, time-and-materials, retainers)

Next, apply realistic collection curves. For example: “Of invoices issued this week, 20% is collected within 7 days, 60% within 30 days, and the remainder within 45–60 days.” If the curve is unknown, estimate it and refine it monthly using actuals. The Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED) tracks delinquency measures that reinforce a key point: payment behavior shifts with economic conditions, so collection assumptions should be revisited.

Seasonality also needs to be modeled explicitly. A retailer may see receipts surge during holidays and returns spike afterward; a contractor might collect at project milestones. Rather than averaging the year, use a seasonal multiplier (e.g., 1.3× for peak months, 0.8× for slow months) and recalibrate it after each season.

Model outflows: payroll, rent, inventory, taxes, and debt service

Compared to inflows, outflows are less flexible—many are fixed, scheduled, or legally required. Accurate cash planning depends on mapping when money actually leaves the account, especially for “lumpy” payments that don’t appear evenly in monthly P&Ls.

Schedule non-negotiables precisely by pay date, due date, and draft date (ACH timing matters). Key categories to calendar:

- Payroll: wages, employer taxes, benefits, contractors (often the largest weekly swing)

- Rent and occupancy: rent, CAM, utilities (often clustered early month)

- Inventory and COGS payments: supplier bills, freight, 3PL/fulfillment

- Taxes: payroll deposits, sales tax, estimated income taxes

- Debt service: principal/interest, equipment loans, merchant cash advances

A frequent planning error is treating annual or quarterly bills as “small” because the P&L spreads them via accruals. The bank account doesn’t. Insurance renewals, license fees, property taxes, and software renewals should show up as cash events in the week they’re paid, even if the expense is amortized for accounting purposes.

Inventory businesses need additional visibility into reorder-related cash commitments. With lead times of 6–10 weeks, today’s purchase order becomes next quarter’s cash constraint. Track expected vendor payments by shipment date (deposit, on ship, Net terms after receipt) so the forecast reflects how suppliers actually bill.

Working capital levers: AR collections, AP timing, inventory turns, and deposits

When a 13-week forecast shows a dip, the goal isn’t panic cutting—it’s selecting the least damaging lever. Working-capital moves improve liquidity by changing timing rather than sacrificing long-term capability.

Collections is typically the fastest lever, so start there and tighten process before relationships:

- Send invoices the same day work is delivered (or automate milestone billing)

- Adopt payment links and require saved payment methods for repeat buyers

- Create a cadence: reminder at 3 days before due, follow-up at 3/10/20 days past due

- Escalate by policy (pause work, require partial prepay) rather than ad hoc decisions

Next, improve payables timing without damaging vendor trust. Negotiating terms based on reliability (“we always pay on day 30; can we move to Net 45?”), batching payments weekly to avoid surprise drafts, and prioritizing payments by operational risk can make cash flow more predictable. Done well, AP discipline reduces late fees and improves consistency for both sides.

Product businesses often feel the biggest drag from inventory. Slow-moving SKUs lock cash while increasing storage and obsolescence risk. Improve turns by using ABC categories (A = must-stock fast movers, C = buy-to-order or discontinue), tightening reorder points, and discounting strategically to convert dead stock into cash. As Gartner supply chain research notes, excess inventory repeatedly drives working-capital pressure during demand swings, which makes SKU-level visibility a high-return habit.

Billing structure can also change liquidity quickly. Service businesses often reduce cash gaps by shifting from “paid at the end” to retainers, progress billing, or materials deposits. Even a simple policy—such as 30% upfront on projects over a threshold—can narrow the gap created by weekly labor and subcontractor payments.

Cash buffers, credit lines, and scenario thresholds for decision-making

Timing shocks happen even in well-run companies: a delayed customer payment, an unexpected repair, or a seasonal lull. A defined cash buffer, responsible credit usage, and clear decision thresholds help you respond early—while options are still available.

Set two targets: a minimum operating floor (for example, 2–4 weeks of essential outflows) and a stability buffer (often 6–12 weeks, based on volatility and credit access). Rather than choosing numbers emotionally, size these targets from your forecast by identifying the biggest weekly outflow cluster (often payroll + rent) and ensuring one disruption doesn’t force high-cost borrowing.

A revolving line of credit can be helpful if it’s governed by rules:

- Use the line for timing gaps (receivables lag), not persistent losses

- Set a maximum utilization target (e.g., no more than 50–60% outside peak season)

- Plan a “clean-up” period (pay down to near-zero at least once per year if feasible)

- Track borrowing base constraints (AR eligibility, concentration limits)

Define scenario thresholds that trigger action instead of debate. For example: if projected ending cash falls below the operating floor in any of the next four weeks, freeze discretionary spend; if it drops below the stability buffer, run a collections sprint and defer noncritical inventory; if it goes negative, activate pre-agreed steps (draw on the line, renegotiate vendor timing, pause hiring). As Peter Drucker observed:

“What gets measured gets managed.” — Peter Drucker

With thresholds in place, weekly cash reviews become more operational: the forecast doesn’t just identify risk—it triggers specific, pre-planned responses based on data.

Budgeting, Forecasting, Tools, and Common Mistakes in Small Business Financial Planning

Cash visibility is only useful if it changes how you spend, hire, and commit resources. To bridge the gap between insight and control, you need a system that converts trends into commitments: a budget with rules, a forecast that updates, and tools that reduce manual work.

This section focuses on execution: selecting a budgeting method that matches volatility, building forecasts from drivers you can influence, keeping data current with lightweight tools, and avoiding mistakes that quietly undermine otherwise “good” plans.

Choose a budgeting method (zero-based, incremental, rolling) and set variance rules

The right budgeting method depends less on preference and more on predictability. To make budgeting useful throughout the year, choose an approach that fits your volatility—and establish variance rules so you don’t renegotiate every line item each month.

Zero-based budgeting rebuilds expenses from scratch, requiring each cost to be justified for the next period. It’s especially effective after a cash crunch or when addressing “subscription creep,” though it can be time-intensive. Many businesses apply it primarily to overhead and discretionary spend (software, contractors, travel) while keeping predictable categories (rent, base payroll) simpler.

Incremental budgeting adjusts from last year (or last quarter). It’s efficient in stable operations, but it can also lock in inefficiency. When demand is seasonal or uncertain, rolling budgets (always budgeting the next 12 months) can be more practical because they force regular reallocation instead of annual lock-in.

Whichever method you choose, set variance rules in advance so responses are consistent. A simple approach uses both percentage and dollar thresholds, with clear ownership:

- Green zone: within ±5% or ±$500 of plan (monitor only)

- Yellow zone: 5–10% or $500–$2,000 (explain driver; adjust forecast if recurring)

- Red zone: over 10% or $2,000+ (decision required: cut, re-price, re-scope, or re-invest)

To avoid “budget theater,” connect meaningful expense lines to drivers such as headcount, units shipped, billable hours, ad spend per lead, or square footage. Variances become more informative when they point to operational causes rather than simply “over” or “under.”

Forecasting approaches: driver-based models, cohort trends, and sensitivity analysis

Budgets express intent; forecasts describe what is likely given current evidence. For smaller teams, a few straightforward methods—driver-based models, cohort trends, and rapid sensitivity testing—often provide the best balance of accuracy and effort.

A driver-based forecast starts with operational inputs and converts them into dollars. An agency might model revenue as billable hours × realized rate × utilization, while a product company might use orders × average order value and incorporate return rates and fulfillment costs. When results diverge, the model helps pinpoint whether the issue is volume, price, capacity, or conversion.

For subscription and repeat-purchase businesses, cohort trends often improve accuracy. Customers are grouped by start month, and retention, expansion, and churn are tracked over time. Instead of forecasting “sales” as a single line, you forecast how existing cohorts typically behave plus how new cohorts tend to mature. Investor research such as Bessemer Venture Partners (Cloud Index/Atlas) frequently emphasizes retention and net revenue effects because churn often dominates long-term outcomes.

Finally, use sensitivity analysis to test the assumptions most likely to break liquidity—especially collections speed, gross margin, and payroll growth. Complex simulations aren’t required; a simple table often reveals where uncertainty matters most:

- What happens if DSO increases by 10 days?

- What if gross margin drops 3 points due to discounting or freight?

- What if hiring slips revenue out by 60 days but adds payroll immediately?

“Forecasts may tell you a great deal about the forecaster; they tell you nothing about the future.” — Warren Buffett

The objective isn’t perfect prediction; it’s knowing which levers deserve weekly attention because they move cash the fastest.

Essential tools: spreadsheets, accounting software, dashboards, and automation

Tools don’t replace judgment, but they can reduce delays and prevent errors that quietly distort decisions. A practical stack—kept as simple as possible—helps the plan stay current without becoming a second job.

Spreadsheets (Excel or Google Sheets) remain the fastest way to build a 13-week cash view, scenario toggles, and sensitivity tables. For maintainability, separate tabs into assumptions, actuals import, forecast, and charts. Lock formula cells, use data validation, and keep a change log so “why did this number move?” has a clear answer.

Your accounting system should remain the source of truth for actuals. Systems like QuickBooks, Xero, or Sage can support consistent categorization, classes/locations, and scheduled reporting. Configuration is the differentiator: clean vendor rules, consistent mapping, and disciplined use of dimensions (tags/classes) so margin and overhead appear clearly without manual recoding.

As transaction volume grows, dashboards and automation can reduce manual work. Common additions include:

- Dashboards: Power BI, Looker Studio, or Tableau for KPI trends (CCC components, margin by line, aging)

- Cash visibility: bank aggregation and alerts (e.g., daily balance thresholds)

- AR automation: invoice reminders, auto-chasing, and payment links to reduce friction

- Integrations: tools like Zapier/Make to sync CRM → invoicing → reporting, reducing re-entry errors

When prioritizing automation, focus on tasks that are both frequent and error-prone: invoice creation, payment reminders, and recurring accrual-like cash events (tax deposits, renewals). Protecting timeliness is often more valuable than adding complexity.

Common mistakes and how to avoid them (overoptimism, ignoring cash timing, under-taxing)

Planning breaks down in predictable ways, especially when P&L logic feels intuitive and cash logic does not. The most effective prevention is to identify the common traps early and pair each with a simple control.

Overoptimistic revenue assumptions often appear as “hockey stick” plans without capacity or conversion support. Anchor forecasts to real constraints—lead volume, close rates, delivery capacity, and average time-to-cash. When the model depends on a step-change, document the mechanism (new channel, price increase, new hire) and add a lag before it affects receipts.

Ignoring cash timing is a frequent cause of crisis: profitability can coexist with cash stress when DSO rises, inventory builds, or large bills cluster. The remedy is procedural: reconcile the 13-week forecast to bank activity weekly, and require any new commitment (hire, software contract, inventory buy) to show cash impact by week—not just “monthly expense.”

Under-taxing is more common than many owners expect, especially for pass-through entities during growth periods. Treat taxes like a vendor by automatically setting aside a percentage of receipts into a separate account, then true-up quarterly with your advisor. The IRS guidance on estimated taxes emphasizes that many taxpayers must pay periodically through the year rather than catching up at filing time.

Additional pitfalls worth keeping on a checklist:

- Mixing one-time items into operating trends (masking true performance)

- Confusing booked revenue with collected cash (especially with deposits and retainers)

- Not budgeting for replacements (equipment, vehicles, laptops) and other inevitable capital needs

- Letting subscriptions proliferate without an owner and renewal review date

A useful rule of thumb: if a surprise costs more than one day of leadership attention, it deserves a line in the next planning cycle.

Operating rhythm: weekly cash review, monthly reforecast, quarterly plan updates

Financial plans stay useful through rhythm, not willpower. A lightweight cadence keeps forecasts honest, surfaces issues early, and prevents the annual budget from becoming irrelevant by February.

Start with a weekly cash review (20–30 minutes) focused on the next four weeks: the largest inflows at risk, the largest scheduled outflows, and any threshold breaches. Keep the discussion operational by assigning specific actions such as “call the top five past-due accounts,” “move the vendor payment batch to Friday,” or “delay noncritical POs until collections clear.”

Follow with a monthly reforecast (60–90 minutes) that updates the next 3–6 months using actuals and revised assumptions. Review margin by line, payroll vs. capacity utilization, and the top recurring variances. Then choose one of three outcomes: recommit to the plan, reallocate resources, or reset targets with explicit tradeoffs.

Use the quarterly update to connect strategy and numbers. Revisit pricing, channel mix, hiring plans, and capital needs, and re-score key risks (collections, input costs, demand). A one-page financial scoreboard with 8–12 metrics and targets helps keep quarterly planning grounded in evidence rather than narrative.

With this cadence in place, small business financial planning becomes less about predicting the future and more about maintaining a repeatable decision system that detects pressure early and allocates cash intentionally.

Turning Financial Planning into a Repeatable Advantage

Long-term consistency is what turns planning into an advantage. Keep the system simple and disciplined: clean data, explicit assumptions, and a steady cadence of review that links cash timing to operational decisions. With that in place, you gain decision-ready visibility—and the ability to adjust early, before small gaps become expensive problems.

Bibliography

Bessemer Venture Partners. “Atlas.” Accessed February 9, 2026. https://www.bvp.com/atlas.

Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis. “Delinquency Rate on All Loans and Leases, Commercial Banks.” Accessed February 9, 2026. https://fred.stlouisfed.org/series/DRALACBN.

Internal Revenue Service. “Estimated Taxes.” Accessed February 9, 2026. https://www.irs.gov/businesses/small-businesses-self-employed/estimated-taxes.

U.S. Small Business Administration. “Financial Management.” Accessed February 9, 2026. https://www.sba.gov/.